In 2017, Theresa May’s Conservative Party spent eighteen and a half million pounds on its General Election campaign,[i] earning it the world record for the most expensive bullet ever retrieved from a woman’s foot. A few days later, Mrs May was forced to buy DUP support at a cost of £100m per MP, the most money spent trying to save a face since the preparations for Michael Jackson’s final tour. Political campaigns can be very expensive.

There are two widely acknowledged problems with political parties and money. The first is how they raise it and the second is how they spend it.

Raising it.

The first problem needs little elaboration. During the 2017 General Election, for instance, 83 people on the Times Rich List donated £12m to the big three parties, plus UKIP and the Greens. Unsurprisingly, £5.5m of the loot went to the Tories, with the LibDems taking £3.5m, and Labour £2.2m.[ii] Labour also raised money from affiliated trades unions, while all parties routinely collect smaller donations and membership fees. It’s donations that concerns us here.

Election 2017: Theresa May shares a joke with her campaign managers.

The taint of corruption around party finances has lingered long; with legislative remedies beginning with the Corrupt and Illegal Practices (Prevention) Act of 1883. Somewhat more recently, the Honours (Prevention of Abuses) Act of 1925 addressed the specific problem of parties selling titles for cash, although with only limited success, as the ‘Cash for Honours’ scandal of 2006 fulsomely demonstrated. In 2000, the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act created the Electoral Commission, which now regulates party finance and electoral probity.

That political donations should be kept free from graft and rascalism has few dissenters, but it is commonly accepted that parties should have to raise their own funds. Support for the alternative – full state funding – has long been poisoned by the personal avarice of discontinued MPs like Neil Hamilton, Stephen ‘Cab for Hire’ Byers, and Patrick Mercer whose greed seeps along the gutter of recent political history like saliva from an up-turned trough. There’s widespread cynicism about the democratic cost of such fundraising – what precisely it is that wealthy patrons are buying – but not yet enough to make improper spending of private largesse a greater popular evil than correct spending of the taxpayer’s hard-earned cash.[iii] More on state funding in a moment but it’s not happening any time soon.

Spending it.

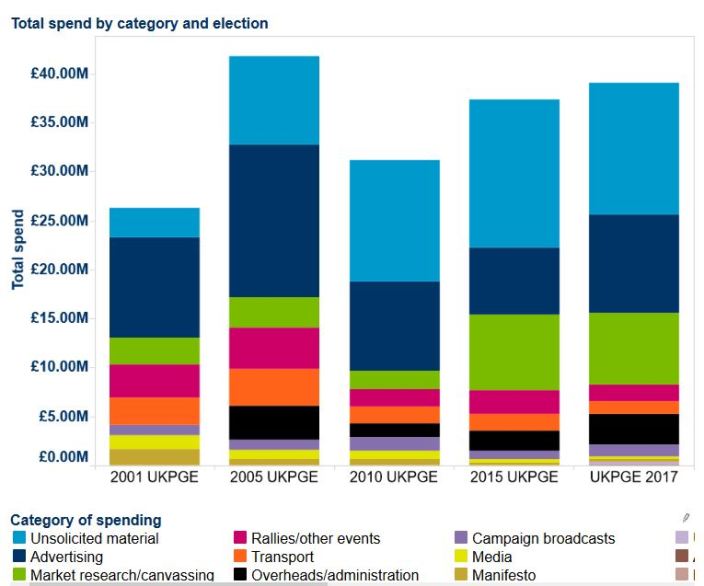

To the second problem, then; what do parties spend all their treasure on? The Electoral Commission chart makes it clear. Of the nine categories included, only transport and administration aren’t some form of political communication or, to use the older word, propaganda (you can see all the categories by clicking here -ignore the split over s. 75 spending).

To the second problem, then; what do parties spend all their treasure on? The Electoral Commission chart makes it clear. Of the nine categories included, only transport and administration aren’t some form of political communication or, to use the older word, propaganda (you can see all the categories by clicking here -ignore the split over s. 75 spending).

One account of the need for political communication, which lives on in the literature to this day, is the work of the celebrated American economist Anthony Downs. In the 1950s, he argued that parties need to build durable coalitions of support among voters who ‘invest’ in them with their votes. However, before buying stock in a party, one first needs to shop around by informing oneself of the competing parties’ positions on key issues. Inevitably, this self-education is time-consuming and, given that one’s own vote makes effectively zero difference to the result, is an ‘irrational’ expenditure of effort for no measurable gain. To counter this problem, political communication acts as a subsidy to the electorate: parties proactively advertise their wares; distilling policies into easily-understood offers that allow the punters to reduce the costs of ‘spending’ their vote on the best deal for them. More on this in a moment.

Winners and losers.

That’s a formal answer to why parties need to raise so much money for communications but let’s ask another question. Who, aside from advertising agencies, benefits from the parties’ need to spend so much money on campaigning? I see four consequences to arrangements as they are.

The first, obvious consequence is that smaller parties can only chirp while the Big Two screech.[iv] Parties spending heavily on their campaigns encourages the other parties to compete but if they can’t their presence in the campaign will likely be reduced. This leads to a diminished field of choice and the possibility of a cartel.[v] True, UKIP is a recent example of a small party that did project a substantial national voice — including a coveted role for Nigel Farage as the Alan Davies of Question Time — even despite the Party’s failure to trouble the House of Commons (other than by reanimating the political corpses of former Tory MPs).[vi] But its reach until the Brexit referendum was aided by a string of sugar daddies[vii] who allowed it to hate above its weight (and, I must concede, by a preternatural gift for melding decades of inchoate grievance into an unbending determination to vandalise the European flag with blood fresh from the nation’s wrists).[viii]

Secondly, the need to spend so much money on campaigning promotes centralised control within parties. To varying extents, local MPs are dependent on their party machine for access to its resources for canvassing, leafleting, local market research, and so on. In the 2015 General Election, the Tories conducted private polling of 80 target seats to provide local candidates with detailed information. Labour, borrowing from the Obama campaigns, constructed a new database and voter profiling system.[ix] Both parties maintained large teams of volunteers to deploy in key constituencies.[x] The threat of being robbed of all this muscle arguably serves as a strong informal way of disciplining MPs and candidates. In the 2017 General Election, so Alex Nunns suggests, the Labour bureaucracy may have in some cases allocated its social media, wide direct marketing, and targeted direct marketing spending at least partly with the intention of bolstering candidates with whom it had a ‘political affinity’ (i.e. being anti-Corbyn).[xi]

A third consequence of parties’ need for large amounts of money is that it allows capital, individual or corporate, leverage over politics. The investment theory of party competition formulated by the American academic Thomas Ferguson holds that parties can only adopt policies that enable them to attract the investment required to run successful campaigns.

“…it is a simple fact that virtually all the issues that both elites and ordinary Americans think about outside of or alongside campaigns – work and employment, free trade or protection, health care, the future of … production, the cities, taxes – are critically important not only to voters, but to well-organised investor blocs, businesses, and industries. And it is another simple fact that many such groups invest massively in candidates.”[xii]

Ferguson proposes an alternative to Downs’s model, arguing that, while voters cannot practicably invest the time required to properly acquaint themselves with all the issues that affect their interests, capital can. Much like business can give concerted attention to an issue in a way that community activists cannot (as I’ve discussed here, for instance), big business has the resources and focus to thoroughly evaluate candidates and parties to reward those who best serve their interests. This (along with slick lobbying operations and corporate PR generally) naturally influences the boundaries of political debate; promoting some issues and suppressing others.

Fourthly, I think Downs’s market analogy is naïve. It neglects in both cases, the true nature of the communication being deployed, which (to borrow from Jürgen Habermas) is not rational but strategic.[xiii] Strategic communication treats people not as ends but as means, either to shift product or to win office. In a word, it’s marketing. If you doubt this in either case, ask yourself how much of political or commercial communication is a simple attempt to explain the merits of a policy or product without recourse to evasion, emotional manipulation or plain deceit. As Aristotle would have noted, marketing runs long on ethos and pathos but very short on logos.[xiv] Negative campaigning, gimmicks, emotional manipulation, audience research, market segmentation, and targeted messaging impoverish genuine political debate and corrode collective critical faculties. We become a pack of dogs who salivate or snarl whenever the bell is rung (or a whistle blown).

There we have the problem as I see it. Parties prospering through donations is fundamentally undemocratic since, however stridently some protest to the contrary, voting is not the same as spending money. The vote is a token that levels the electorate because everyone gets just one. In the current system, wealth entrenches wealth as parties rent-seek from high-spending minorities while neglecting the stony majority.

You might argue that this doesn’t have too much effect since all parties are heard to some degree (especially under election broadcasting rules, which undoubtedly benefitted Jeremy Corbyn in 2017) and the diligent voter can discover whatever she needs to with a little research. But if the ability to deploy millions in advertising confers little advantage why bother? Some might also argue that individual donations reflect wider support in the country: the more support a party has the more donations they’ll receive and so the louder their voice becomes. But this is to put the electoral cart before the democratic horse. Democracy should not be about allowing popular messages to be heard more loudly but allowing all messages to be evaluated equally.

Keeping them honest.

The parties can be kept honest in two ways: by keeping an eye on how they raise money and a reign on how they spend it.

To take the first approach, the most widely-touted remedy is state funding. In fact, I used the phrase ‘full state funding’ earlier with good reason. Though not widely known, opposition parties in the Commons receive state funding for carrying out their parliamentary duties, research, formulating policy, travel expenses, and so forth. This ‘Short Money’ was introduced in 1975 and is paid to any opposition party with at least two MPs.[xv] There’s an involved formula for calculating payments but, in 2016-17, the Labour Party received just under £6.5m and the LibDems half a million. Somewhat farther from the buffet table, the Greens and UKIP received £216K a piece.[xvi] One might develop this into a formal system of state funding (encompassing the ruling party) and allocate funds for extra-Parliamentary activity. Naturally, as the current system rewards parliamentary incumbency, one would need to find an equitable way to extend it to parties without a seat.

There are several drawbacks to state funding. One is that a background level of mismanagement and expenses-rigging would occur but that is already the case. In fact, it might be preferable for the taxpayer simply to accept MPs’ more venal tastes but take advantage of state buying power. At least a heavily-discounted bulk purchase of Columbian cocaine would finally give Liam Fox a post-Brexit trade deal to crow about. And a similar Parliamentary five-year tender for prostitution services would surely be welcomed by upstanding members on both sides of the House.

Another drawback might be that, as in rentier states, state funding runs the risk of making the political class flabby and unresponsive. Relieved of the need to rattle a tin at donors big and small, parties will sit back and live on benefits. Worse, as the parties would be responsible for drawing-up the rules, this would only increase the tendency of the main parties to act as a cartel. I suspect, however, that both these objections would be firmly at the back of a public mind wholly dominated by one preeminent demurral: “Why should we give those fuckers a penny?”[xvii]

The other approach, spending controls, is also partly in use. Earlier this month, the Electoral Commission fined Leave.EU £70,000 and referred its CEO to the police for failing to report at least £77,000 of campaign spending.[xviii] In 2017, the Commission also fined the official Remain campaign and the LibDems for undeclared spending during the EU referendum campaign and the Conservatives £70,000 for breaches during the 2015 General Election and by-elections in 2016.

Nationally, registered parties may spend no more than £30,000 for each constituency they contest. This means parties fighting all 650 seats have their spending capped at £19.5m but that money doesn’t have to be spent equally on each constituency. Locally, individual candidates may spend an additional £10-16k in the 25 days before a General Election but, for a by-election, the limit is £100k.[xix] Fines are available for breaches of these laws and, if sufficiently grave, theoretically the local result can be voided and the election re-run. There is a defence, however, which applies if the election agent committed the offence without the ‘sanction or connivance’ of the candidate. Which, of course, will always be the case.

A different way?

The shared premise of controls on both how parties raise and spend campaign funds is that it is necessary and proper that parties spend money on campaigning. But what if one were to take a different view and argue that political campaigning — or, more precisely, the promotion of genuine, democratic debate — is too important to allow it to be contaminated with money? Formally at least, elections are supposed to be competitions between competing sets of policies, even visions for the way life should be. Money distorts this competition for three reasons. Firstly, if money confers advantage and is for any reason unevenly distributed then advantage will be unevenly distributed. Secondly, if the flow of money going into the parties reflects the existing distribution of power within society, then those with power will be privileged. Thirdly, and most fundamentally, using money to make one policy more prominent or appealing at the expense of another runs the risk of that other idea not being given its proper consideration. This is labouring an obvious point, I know, and also assumes that the campaign is about actual policy at all and not merely personality or ‘values’.

I’m not arguing that parties should be barred from issuing political communications. But would it not be better if a party’s voice, certainly at election times, had nothing to do with how much moolah it could muster? Instead, imagine if each party meeting certain eligibility criteria (fielding a minimum of candidates for instance) received an allocation of free communications but was barred from purchasing more. This allocation would include the printing and delivery to all homes of its manifesto, a certain number of party political broadcasts, access to hustings, money for events, and social and old media advertising. Locally, each candidate mustering over a certain threshold of signatures would get an equal allocation of materials and promotion. Personally, I would ban local and national polling in the month before a general election so that, rather than fine-tuning a message to get elected, parties would instead have to stake out a position and campaign for it.

Importantly, there would be no state interference with the content of the message, only parity of prevalence. Parliament would inevitably have to set the broad outline and intent of the policy, but the practical details and enforcement could be left to the Electoral Commission. The number of news media appearances — and hence the power of the corporate press to pick winners — would be harder to regulate but democratising the media is a separate issue.

This is a sketch rather than a solid, worked-out policy proposal but I think the idea would address some of the problems of the current system. Shorn of the need for campaign donations, parties would be far less in-hock to business, especially if capped state-funding for administrative costs were standardised. The debate between the larger and smaller parties would also be evened-up: a good thing, as how large a party is has no necessary connection with the merit of its position. If the means of campaigning were roughly the same, then the focus would have to be on the content of what each party was saying. It wouldn’t stop parties trying to bribe and mislead the electorate, but a campaign stripped of a lot of the flimflam might help the substantive issues come to the fore, leading to a more informed and responsible public.

Which is why it’ll never happen, of course.

Notes.

___________

[i] Labour spent £11m and the LibDems £6.8m. Peter Walker, “Tories spent £18.5m on election that cost them majority,” The Guardian 19th March 2018, available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/mar/19/electoral-commission-conservatives-spent-lost-majority-2017-election

[ii] Alastair McCall , “Britain’s richest give £12m to parties fighting election,” The Times, 21st May 2017, available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/rich-list-2017-britains-richest-give-12m-to-parties-fighting-election-jn0dzpvms

[iii] Author unknown, “Britain’s parties should be funded by the state,” Financial Times, 19th February 2015, available at https://www.ft.com/content/6e3c067e-b837-11e4-b6a5-00144feab7de

[iv] And the incumbent party will receive more coverage as both a party and as the Government.

[v] See for example, Katz, R.S., Mair, P., (1995), ‘Changing Models of Party Organisation and Party Democracy The Emergence of the Cartel Party’, Party Politics, Volume 1, pp. 5-28.

[vi] Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless.

[vii] Anna Leach, “Meet UKIP’s 5 biggest donors”, The Mirror, 2nd January 2015, https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/ampp3d/meet-ukips-5-biggest-donors-4909075

[viii] And we may yet see a new small party punch above its parliamentary party if a new ‘centrist’ party, apparently equipped with £50m to ‘break the mould” of UK politics by giving a much-needed voice to marginalised and powerless multimillionaires like Simon Franks, ever emerges into the light (Michael Savage, “New centrist party gets £50m backing to ‘break mould’ of UK politics,” Guardian 8th April 2018, available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/apr/07/new-political-party-break-mould-westminster-uk-brexit

[ix] Andrew Mullen (2015) “Political consultants, their strategies and the importation of new political communications techniques during the 2015 General Election,” in Daniel Jackson and Einar Thorsen (eds) “UK Election Analysis 2015: Media, Voters and the Campaign” The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community, p. 42.

[x] Tim Ross (2015) “Why the Tories Won: The Inside Story of the 2015 Election,” Chapter Three. The Tories, for instance, spent hundreds of thousands on “Team 2015,” which borrowed psychological motivation techniques (including ‘chivvying teams’ of volunteers supplied by accountancy behemoth PriceWaterhouseCoopers) from the team behind London 2012. The team was 100,000 strong, with groups bused around the country to campaign in target constituencies in what its organiser, Grant Shapps, called a ‘ground war’.

[xi] Alex Nunns (2018) “The Candidate” (2nd ed.), OR Books (London), pp. 335-38.

[xii] Thomas Ferguson (1995) “Golden Rule. The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems,” University of Chicago Press, p. 8.

[xiii] See Habermas’s “Theory of Communicative Action, Volume 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society: Reason and the Rationalization of Society” and especially “The Theory of Communicative Action, Volume 2: A Critique of Functionalist Reason”. His “Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere” is also interesting.

[xiv] See Aristotle’s “Art of Rhetoric”.

[xv] Or if they have one MP but received more than 150,000 votes in the previous General Election.

[xvi] House of Commons Research Briefing, “Short Money” 19th December 2016 available at http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN01663 There’s a related allocation in the Lords, known as the Cranborne Money.

[xvii] There have probably been a few third ways proposed. In the US, for example, various experts have suggested systems in which each voter is given a voucher, which they can donate to the party of their choice. The voucher is then redeemable for cash but with enhanced safeguards attached. Seattle have been trying a variant of this for several years, which was touted to get ‘big money’ out of politics. I shan’t dwell on it here but as corporations are still able to make cash donations, the ‘big money’ isn’t getting any smaller.

[xviii] Electoral Commission, “Leave.EU fined for multiple breaches of electoral law following investigation” 11th May 2018, available at https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/i-am-a/journalist/electoral-commission-media-centre/news-releases-donations/leave.eu-fined-for-multiple-breaches-of-electoral-law-following-investigation

[xix] FullFact, “Democratic deficit? The rules on election spending,” 10th May 2017, available at https://fullfact.org/law/election-spending-rules-conservatives-electoral-commission/

Excellent and witty. A great read first thing in the morning.

I see that you read Ross’s (2015) ‘Why the Tories Won’ but the follow-up ‘Betting the House’ is also quite revealing and a further explanation of where almost 25% of the electoral spending went for May.

“Lynton Crosby’s campaign for Theresa May was not the winning one he’d hoped but the PR magnate and his company made £4m for two months of work. The Australian PR man was the one who won it for David Cameron in the previous election.” [http://www.ephemeraldigest.co.uk/2018/02/betting-the-house-review/]

I believe that it was around £6m spent on Cameron’s campaign but that took place over a lot longer than two months.

Another effect, I was reading about over the weekend, was the increase in familiarity that ‘marketing’ of candidates provides but that also points to the effect being lower/slighter in incumbents. Presumably because they already get some coverage. https://www.press.umich.edu/pdf/0472099213-ch8.pdf

I was listening to Chomsky talk about Ferguson two days ago and hadn’t read a reference to Downs since university nearly two decades ago now. If we’re going to have a depressing system then at least it’s nice to have something good to read about it.

Thank you, David.

LikeLike

Hello Joanna,

thank you for leaving such a constructive comment and for your kind words. I’m aware of ‘Betting the House’ but I’ve not read it. I had to go back check my memories of Downs as it had been a long time for me as well. I really could do with doing another degree in politics but, this time, not getting drawn to the dark side. ..

LikeLike