I’m old enough to remember video tape with affection. My family acquired its first video cassette recorder around 1982 when the novelty was still vivid. It was VHS, front-loading, the size of a small family hatchback and by modern standards almost Heath-Robinson in it brute mechanical beauty.

It’s hard to explain why I feel such nostalgia for what objectively was a clumsy cacophony of rubber, metal, and plastic but I do. For the six year old me, it was irresistibly encrusted with buttons, knobs, sliders, and dials. The customary shopfront of its principal controls – play, rewind, and pause – were pleasure enough but other treasures were hidden beneath a hinged flap on the lower front and a detachable panel inset in the top. Beneath these glittered the more exotic controls like ‘tracking’ and ‘input,’ eight mechanical tuning dials and the ‘AFT’ button.[i] When Channel Four was born in November 1982, my dad had to get on his hands and knees, pop the top panel and seek out primordial Countdown through the crashing surf of static.

I can remember pressing the Standby button, opening the door and seeing tantalising glimpses of the illuminated heads, capstans, and spindles within. I can hear in my head, as clearly as you can remember your favourite song, the refrain of its mechanism as I pressed a tape into the front door and watched as it was drawn inside the beast. Sometimes it was a video mechanism, other times its was the landing bay door of a secret base.

It even had a ‘remote’ control: play, pause, fwd, rew, and rec attached via a 3ft cable that plugged in at the back and, once passed over the machine, afforded one the luxury of operating the machine from about 18 inches away. I’m even fond of the problems that afflicted its dotage (and my teenage years when it became mine alone) – the way it would sometimes crimp the edge of the tape, irreparably knackering the sound on some of my favourite tapes.

These were the days when I had a library of blank cassettes, some labelled (most not) and packed with recordings of Doctor Who and Star Trek: The Next Generation. The E120, the workhorse E180, the mighty E240s. The Scotch ‘lifetime guarantee’ fronted by an amiable skeleton. The etheric and unrepeatable[ii] magic of TV, captured and tamed in a shiny box like a ghost trapped by Venkman, Stantz, Spengler, and Zeddemore.

I remember, into the 90s, the archaeological pleasure of watching old tapes, especially those borrowed from friends, through to the end. The first recording would finish, there’d be a wash of static, and then the fag end of the recording beneath would slide into view. Then another and another. I’d often watch tapes through right to the point when they’d click off and rewind. One minute, you’re watching ITV’s bowdlerised 90s cut of Heartbreak Ridge (complete with the minced oath, ‘maggot farmer’), then you’re transported into the technicolour fantasy of an 80s ad for Kellogg’s Fruit n Fibre (with one with Ross Kemp) or those weird 80s Weetabix commercials in which booted and braced skinhead biscuits of wheat would intimidate other cereals (and we accepted this as normal).

At the weekends, I was allowed to accompany my dad to the Six Hills Video Shop and choose a title from the seemingly enormous array of display cases that bejewelled its walls. Only from the Us and PGs, of course, although I was obviously far more enticed by the 15s and 18s, which all had far more exciting and stimulating covers (especially some on the top shelf in one corner) and were alluring because they were forbidden.

It’s all gone now. Funai Electric manufactured the last video recorder in July, 2016. While there is a small but enthusiastic market for old video tapes, particularly the more obscure horror movies, I doubt there’ll ever be a ferrous oxide resurgence to mimic that of vinyl. Yet, our language is an analogue recording of history. I still hear people talk about ‘taping’ and ‘rewinding’ and we’ll still be discussing the medium of film long after celluloid takes its place next to wax cylinders and daguerreotypes. One day film will exist only in films.

The big selling point of video recorders was convenience and, notably, control. Watch what you want to watch, when you want to watch it. Don’t be a slave to those damned TV channels but the master of your own viewing pleasures. As Troy McClure said to Delores Montenegro (in ‘Calling All Quakers’) ‘have it your way, baby.’

Fast forward thirty years and we’re now in another revolution of convenience and ‘control.’ The age of the DVD and the brief blu dawn are coming to an end and now we are dipping our toes in the Great Stream. We now watch even more of what we want to watch, when we want to watch, and without a chilly walk to the video shop or the need to endure the crunching, chattering rabble at the local flicks. We watch, listen, chat, and shop online. But how much of the new control is real?

It’s easy to focus on the petty irritations of the digital world. Netflix’s co-founder recently

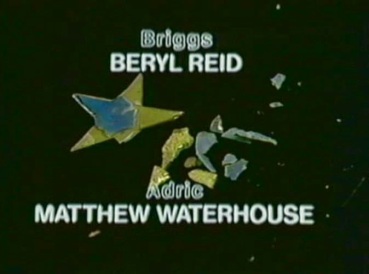

Silent credits attend the death of Adric in the 1982 Doctor Who story, Earthshock

declared their aspiration that one day it would ‘get so good at suggestions that we’re able to show you exactly the right film or TV show for your mood when you turn on Netflix.’[iii] But what if I aspire to read the credits uninterrupted? What if I think that the programme makers might sometimes use the credits for dramatic effect? Instead Netflix, like an overeager waiter, whips away the programme and algorithmically catapults me toward the next course. It’s not wholly new, of course; even on terrestrial TV credits have been squeezed for years by the cajolery of continuity chatterers. But it’s still annoying.

Trailers have always been part of home media. They were there in the VHS days but at least fast forwardable. Nevertheless, imagine visiting a Blockbuster and having a doorman compel you to watch one before you even reached the shelves. This is now what the Android Amazon Video app does at least once per day. Yes, one can stop it once it has started but one cannot stop it from starting. At least at the cinema people can use the adverts and even the trailers to have a conversation, check their phone, or return to the foyer to secure yet more food. Much as they do with the eventual film.

We tolerate behaviour online that we would likely never put up with in person and here I’m not discussing the hourly scorching belligerence of ‘social’ media so well summed up in this video. I mean the behaviour of companies online. Imagine for instance that, near the end of your weekly shop, a store assistant blocked your path and wouldn’t let you get to the checkout until you’d accepted or rejected a list of items in which she thought you might be interested. I think most people would find that hectoring and coercive yet it’s precisely what one has to accept in order to shop online with Sainsbury.

Worse still, imagine the indignity, the sense of violation you would feel if someone broke into your house and stole your CDs. Imagine then instead how much worse you’d feel, how much more soiled, degraded and sullied, if instead of perpetrating such a theft – or merely having a shit on your couch – they left you an album by U2.

Speaking of music, some of you who’ve used the Amazon Music Player might have noticed that it has a subsidiary function, carefully hidden, of allowing you to actually play the music you’ve purchased. Its core function, of course, is to pelt you with inducements to buy more music, preferably via a subscription. This is quite reasonable since, putting chummy marketing aside, Amazon’s sole objective is to persuade you to take money out of your account and put it in theirs. The product itself is a mechanism for selling you more products (again, not new but accelerated online). Helping you to actually listen to your music is very much a secondary concern in what should really be called the Amazon Music Seller. Apps are less like faithful servants and more like pestering children.

“I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

1) Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2) Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3) Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

Douglas Adams –The Salmon of Doubt.

Lest I simply sound like a grumpy old man adumbrating a litany of my peeves, let me make clear that there’s a political edge to my grousing; namely increased control masquerading as choice. The range of baubles for us to play with has increased but the price is that our leisure time – socialisation, entertainment, education and consumption – occurs conveniently on something else’s property. We’re shopping, playing, watching, chatting and searching by their rules. We’re steered where they allow us to go, finding what they want us to find, knowing what they want us to know. Our physical space has already been colonised – what isn’t owned by government is owned by private capital, public town squares have already become private malls. Now cyberspace is heading the same way (and with a massive in-built head start). Sound overblown and conspiratorial? Perhaps today -but tomorrow?

One of the great sleights of hand in recent years, for instance, has been the promotion of ‘the cloud’ – with all the connotations of ownerless neutrality this inspired piece of thought-steering conjures. After all, nobody owns a cloud; it must just float above us like some beneficent 21st century commons. In fact, the cloud is a network of servers belonging to commercial companies ranging from relatively modest independents to the GAFA behemoths of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. Of course, invitations to store one’s data in ‘the cloud’ sound much more benign that ‘on our servers.’

Well, OK, storing one’s property on someone else’s turf isn’t necessarily a one way ticket to Oceania, is it? After all, people dump their shit in Big Yellow Storage all the time without having to affirm that they love Big Brother. Except that it’s no longer your property. No, that film you bought last night from Amazon isn’t yours. In fact, you’ve merely leased it for an indefinite period. Now, you might argue that it was never really yours before. The contents of DVDs, books, CDs, and VHS were all copyrighted – yours to own but subject to strict conditions – so what’s really changed? Well, check Amazon’s T&Cs – they can remove your purchase at any time. Unless you download it to your own storage, you don’t have the unconditional possession that you had over an Amaray-enclosed disc. You’re not purchasing anymore. You’re renting -on a very long term, granted – but you’re renting. Soon, there’ll be no more borrowing a DVD or a book from a friend and you won’t be taking yours down your favourite charity shop when you’re done, either. Like the message, the medium is now theirs. Your shelves of DVDs, CDs, and books will evaporate into a cloud library hosted (held) within someone else’s property. One day, all visitors will have to judge you by will be some misguided ornaments and your personality.

And the capacity to monitor our viewing habits has also increased. The obvious concomitant of Netflix being able to suggest what we might want to watch is that it knows what we have watched. For most people this is no real practical concern but it’s another piece of infrastructure for a surveillance state, another category of data to add to all the others potentially allowing for a detailed picture of us to be constructed and – ask any lecturer wanting to talk about Brexit – some people are just itching to know as much about us as possible. The next time you binge-watch The Handmaid’s Tale remember that you might be munching Doritos in the prologue.

And what happens when Amazon goes bust? Where will your prized collection go when the company no longer exists? True, other companies might buy out the rights and the infrastructure but they don’t have to and won’t if they don’t think there’s money in it for them. Amazon use a proprietary format for Kindle, for example, so there’s no guarantee you’d be left with anything other than what’s stored on your hardware. And when that dies?

Video tapes, CDs, and even books are standards based. So long as your equipment complies with those standards you can read the content. A CD manufactured to the Red Book standard should play on any CD player. Region codes aside, a DVD of The Force Awakens will play on any machine. The latest Dan Brown novel is accessible to anyone who can read, although obviously appreciated to its fullest extent by those who cannot. Streaming and download services rely heavily on proprietary file formats to ensure that material isn’t shareable. There are presently exceptions but how long will they last? Look at the stranglehold (now slipping) that Microsoft has had on word-processing by making sure its file .doc and .docx formats are as opaque as possible.

Digital content such as films, audio files and eBooks are effectively software with all the (potential for) control and restriction that implies. The apps on a smart TV can be withdrawn during forced ‘upgrades’ when licensing deals expire. So, that £700 set you bought with iPlayer and YouTube built in could be without both one day and there won’t be anything you can do except buy a new TV. And this isn’t a hypothetical -it already happens. Let’s not be in any doubt what this is – the company from whom you think you’ve bought something has taken it back from you. Of course, this may be because of genuinely unavoidable incompatibility but it’s hard to believe that this isn’t also another mechanism for enforced functional obsolescence.

There’s no easy answer to this. The technology isn’t inherently wrong but it is massively corruptible. Nor is it going to go away: people will always be lulled by convenience. Alternatives to digital online consumption as part of our increasingly shut-in economy will wither unless we take positive action to keep them alive. They’ll be seen as troublesome, archaic eccentricities, like wanting to travel around New York without a car or live near an A&E. Being offline and off social media will never be forbidden, merely absurdly inconvenient. You’ll always be allowed to walk off the holodeck but why would you want to when beyond lies only isolation, and dark, dark silence?

There’s no easy answer to this. The technology isn’t inherently wrong but it is massively corruptible. Nor is it going to go away: people will always be lulled by convenience. Alternatives to digital online consumption as part of our increasingly shut-in economy will wither unless we take positive action to keep them alive. They’ll be seen as troublesome, archaic eccentricities, like wanting to travel around New York without a car or live near an A&E. Being offline and off social media will never be forbidden, merely absurdly inconvenient. You’ll always be allowed to walk off the holodeck but why would you want to when beyond lies only isolation, and dark, dark silence?

Notes

__________

[i] ‘Automatic Fine Tuning.’

[ii] Well, repeated a lot less in those days.

[iii] Unknown author, Streaming on screens near you. Can Netflix stay atop the new, broadband-based television ecosystem it helped create?’ The Economist https://www.economist.com/news/business/21705353-can-netflix-stay-atop-new-broadband-based-television-ecosystem-it-helped-create-streaming