Last week, I made a sketch of one of the dominant strains of establishment intellectual thought: disdain for the masses and, by extension, genuine democracy. ‘The scholar,’ wrote the noted American economist Edwin Seligman, ‘must possess priestly qualities and fulfil priestly functions, including political activity’ in order that the people learn their true needs and the means of their satisfaction.’[1]

Democracy is, of course, notoriously difficult to define and I’m not going to take Dahl, Beetham, and Sartori from the shelf now. It’s enough to say that by democracy I mean a thing deeper than merely the occasional popular ratification of political decisions made by elites in a political sphere kept carefully separate from its economic foundations (largely the system we have today). I mean genuine popular participation in the formulation as well as the contestation of policy.

Business has done its best to keep democracy in its place by using two principal tools. First, by lobbying for and buying legislation at source and, secondly, by attempting to control popular opinion. It’s the control of opinion that concerns me here. The problem of business manipulating public opinion was predicted long ago. In 1909 Graham Wallas, professor of economics at the London School of Economics, warned of the consequences should business feel its position threatened by a surfeit of democracy,

Popular election may work fairly well as long as those questions are not raised which cause the holders of wealth of and industrial power to make full use of their opportunities… If they did so there is so much skill to be bought, and the art of using skill for the production of emotion and opinion has so far advanced, that the whole condition of political contests would be changed for the future.[2]

Business’s interest in public opinion arose from the drubbing it took during the Progressive Era (circa. 1890-1920) when ‘muckraking’ journalism had enjoyed a golden age. A succession of often sensational newspaper and magazine articles revealed gouging, quackery, mountebankery, vice, corruption, and criminality. Meanwhile, anti-trust laws challenged property rights and virtually every populist politician made play of their opposition to ‘industrial feudalism’ and the ‘conspirators of Wall Street.’[3] Yet while the middle and intellectual classes had initially been behind using the ‘great moral disinfectant’ of publicity, they soon came to revile it. The Progressives wanted greater social equity but they did not want revolution. Muckraking – to the Progressive eye – soon went beyond smoothing the rough edges from corporate industrialism to having the potential to punch a bloody hole through the capitalist machine and undermine belief in the equity of the business system itself. ‘There is in America to-day,’ wrote Walter Lippmann in 1914, ‘a distinct prejudice in favor of those who make the accusations.’ He continued,

“Big Business,” and its ruthless tentacles, have become the material for the feverish fantasy of illiterate thousands thrown out of kilter by the rack and strain of modern life… all the frictions of life are readily ascribed to a deliberate evil intelligence… that ten minutes of cold sanity would reduce to a barbarous myth.[4]

As Fortune magazine recorded years later, ‘business did not discover… until its reputation had been all but destroyed… that in a democracy nothing is more important than [public opinion].’ Alex Carey argues that, with the extension of the franchise impossible to reverse, business aimed to ‘corrupt’ the electorate by manipulating public opinion. So, business became determined to fight ‘words with words’ and hired former newspapermen to act as publicity advisors. America’s first publicity firm, The Publicity Bureau, was founded in 1900 and over the years that followed a number of larger companies created their own in-house PR departments.

The techniques of early PR were comparatively crude, with unsophisticated dishonesty and whitewash commonplace. Despite the immaturity of the profession, it nevertheless fulfilled Abraham Lincoln’s prediction, that big business would try to ‘prolong its reign by working on the prejudices of the people…’[5] As it developed in the first decade of the 20th Century, PR also took the first steps to moving beyond the simple ‘fact-based’ press agentry approach of the Progressive journalists, to develop a more symbol-orientated approach that would eventually become known by scholars of the field as the two-way asymmetric model or ‘scientific persuasion’.[6]

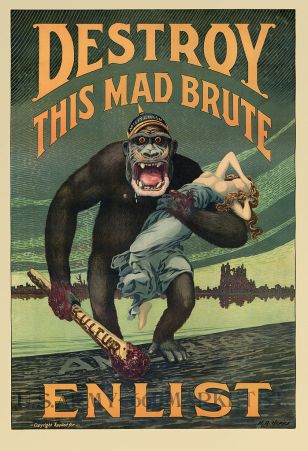

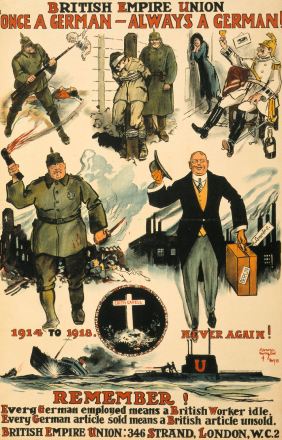

It was World War One that is arguably the single most important event in the development of modern PR, as it marked the formation of the Committee on Public Information (CPI). The US Government was keen to participate in the War, as it and American liberal intellectuals generally had been successfully propagandized by the British. The details of this effort are too extensive to go into here but for years the British Establishment had been drumming into the British people (and American intellectuals) the absolute and unconditional evil of the German people. Sir Norman Angell wrote of a ‘propaganda which did not even pretend to tell the truth since its object was to make us hate the enemy and want to go on fighting him,’ which span fables of Germans ‘boiling down the dead for glycerine and of cutting off babies’ hands for amusement’.

It was World War One that is arguably the single most important event in the development of modern PR, as it marked the formation of the Committee on Public Information (CPI). The US Government was keen to participate in the War, as it and American liberal intellectuals generally had been successfully propagandized by the British. The details of this effort are too extensive to go into here but for years the British Establishment had been drumming into the British people (and American intellectuals) the absolute and unconditional evil of the German people. Sir Norman Angell wrote of a ‘propaganda which did not even pretend to tell the truth since its object was to make us hate the enemy and want to go on fighting him,’ which span fables of Germans ‘boiling down the dead for glycerine and of cutting off babies’ hands for amusement’.

I turn over my note-book to find similar signs that will record the time when men, educated men, took leave of sense and reason. Here are the papers printing long letters protesting violently against giving Christian burial to the Germans brought down in a destroyed Zeppelin… Half a page devoted to a debate in Parliament about leaving an elderly German archaeologist in charge of ancient documents in a museum. There is a great slaughter, it appears, of dachshunds, though one correspondent with qualms wants to be quite sure that the dogs really did originally come from Germany. The Evening News prints lists of those who had undertaken to help feed the children of interned Germans, harrying with headlines (“ Hun-coddlers” was the invention for the occasion) Quakers and others who had been guilty of, explains the Evening News, “ feeding the tiger’s cubs with bits of cake.[7]

Though there was a kernel of truth, presumably, to some accounts of atrocities, the bulk was lies and exaggeration. Little has changed in the hundred years passed: the swindle of Iraqi soldiers ripping Kuwaiti babies from their incubators and leaving them to die on cold floors during the first Gulf War in 1990; the myth of Saddam’s human shredders in 2003; and the tall stories of an impending massacre in Benghazi that were without foundation are but three examples. The bitter rhyme of this unreason, of course, was that the public scepticism of government pronouncements WWI propaganda engendered burned into the late 1930s when stories of real Nazi atrocities reached our shores.

of government pronouncements WWI propaganda engendered burned into the late 1930s when stories of real Nazi atrocities reached our shores.

Whatever the long term folly of the British propaganda, it secured US elite opinion. In the country at large, however, the war was unpopular. Indeed, Woodrow Wilson was re-elected in 1916 on the platforms ‘He kept us out of the war’ and ‘Peace Without Victory.’[8] The working classes, particularly socialists and trade unionists, saw the war as a ‘rich man’s conflict’ and had no yearning – to borrow trades unionist Eugene Debbs’ phrase – to ‘furnish their corpses’ for other people’s property. Similarly, large parts of middle class America were still strongly isolationist and wanted to hold Wilson to his slogans. While privately he had said I will be with you, whatever, a considerable effort was still needed to instil in a timorous America the necessary ‘blazing passion of retaliation.’[9] How time turns the tables.

In April 1917, Wilson put newspaperman George Creel in charge of the newly-formed Committee for Public Information and charged it with securing popular support for the war. Creel had himself urged Wilson to create an agency to coordinate ‘[n]ot propaganda as the Germans defined it, but propaganda in the true sense of the word, meaning the ‘propagation of faith.’’[10] This was to be an effort on many fronts, to reach ‘every community in the United States by written or spoken word or motion picture; until every individual, native, naturalized, or alien, has it seared into his consciousness that this war is a war of self-defence, and that it has got to be master of his every thought and action.’[11]

The CPI’s task was ‘so distinctively in the nature of an advertising campaign’ that they turned almost instinctively the advertisers and the fledgling PR industry.[12] By this time, the advertising industry was moving from simply describing goods and services towards using symbolism and psychology. Rather than merely informing consumers of their wares, advertisers pioneered a ‘seductive mix of words and images’, which they attempted to associate with the public’s ‘emotional lives’, ‘needs, cravings, aspirations, and fears…’

The advertising industry furnished many willing servants who had boasted for some time that, since their techniques moved recalcitrant consumers to buy their clients’ products, they could also sell ideas. The CPI, with half a million dollars, 250 employees, 5,000 volunteers, and 75,000 speakers, supplied articles to 30,000 newspapers, produced 75,000,000 books and pamphlets, and secured $30m of free advertising. Creel’s committee sustained a ‘general climate of thought control,’ facilitated by espionage, censorship, and Sedition Acts under which critics were rounded up and tried.[13] As the President warned his people, ‘conformity will be the only virtue and any man who refuses to conform will have to pay the penalty.’[14]

The catalogue of malign idiocies that ensued almost defeats comprehension. 14 states passed laws forbidding the teaching of the German language; Iowa and South Dakota outlawed the use of German in public or on the telephone; German-language books were ceremonially burned; the Philadelphia Symphony orchestra and the New York Metropolitan Opera Company were refused permission to perform Beethoven, Wagner, and other German composers; German Shepherd dogs were renamed Alsatians; and Sauerkraut became known as ‘Liberty Cabbage.’

And if the intervening century stales some of the poison in that, recall that after the French insisted on more time for UN weapons inspections in 2003, French Fries were renamed Freedom Fries, alleged appeasers were addressed as ‘Monsieur,’ and Country band The Dixie Chicks had their ‘treachery’ punished with ‘possibly the biggest black balling in the history of American music.’[15] Educated people may still be induced to ‘take leave of sense and reason.’

The techniques of the CPI were so successful that Hitler later credited them as a key factor in Germany’s defeat; praising the ‘amazing skill’ and ‘really brilliant calculation’ that achieved such ‘immense results.’[16] Though much of the Committee’s output, following the British model, was later found to be distortion, exaggeration, and lies, at the time it did the job: the beat of propaganda summoned up the blood and drove the nation to war. As Voltaire is generally held to have said, ‘anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit atrocities.’

As the ‘Father of Public Relations,’ Edward Bernays, later said, ‘it was, of course, the astounding success of propaganda during the war that opened the eyes of the intelligent few in all departments of life to the possibilities of regimenting the public mind’.[17] And it is to that I will turn next week.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Fink (1993) “Major Problems in the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. Documents and Essays,”

[2] Quoted in Alex Carey (1995), “Taking the Risk Out of Democracy,” pp. 134

[3] Thomas Frank (2001) “One Market Under God. Extreme Capitalism, Market Populism and the End of Economic Democracy,” p. 37.

[4] Walter Lippmann (1914) “Drift and Mastery,”p. 23-24.

[5] Quoted in David Korten (1995) “When Corporations Rule the World,”) p. 58.

[6] Grunig and Hunt (1984) “Managing Public Relations,” p. 35.

[7] Norman Angell (1926) “The Public Mind its disorders: its exploitation,” p. 31

[8] Larry Tye, L. (1998) “The Father of Spin. Edward L. Bernays and the Birth of Spin,” p. 18.

[9] Norman Angell’s description of the similar fury ignited by propaganda in Britain.

[10] Quoted in Jackall & Hirota (2000) “Image Makers, Advertising, Public Relations, and the Ethos of Advocacy,” p. 13. Creel was referring back to the origins if the word ‘propaganda,’ which stem from the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, a committee established by the Vatican in 1622 to propagate Roman Catholicism

[11] War Information Series, No. 17 (February 1918) excerpted in Delorme & McInnis (1969) “Antidemocratic Trends in Twentieth-Century America,” pp. 66-77

[12] Quoted in Stuart Ewen (1996) “PR! A Secret History of Spin,” p. 113.

[13] Ewen (1996) p. 121.

[14] Z, Mickey (2002) ‘Convincing the Skeptics,’ (https://zcomm.org/znetarticle/convincing-the-skeptics-by-mickey-z/ ).

[15] The Chicks had the temerity to tell a British audience “Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all. We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.” In return, a full-on boycott of their music was called for by pro-war groups. ‘Radio stations who played any Dixie Chicks songs were immediately bombarded with phone calls and emails blasting the station and threats of boycotts if they continued… Dixie Chicks CD’s were rounded up, and in one famous incident were run over by a bulldozer… The Dixie Chicks lost their sponsor Lipton, and The Red Cross denied a million dollar endorsement from the band, fearing it would draw the ire of the boycott. The Dixie Chicks also received hundreds of death threats from the incident.’ http://www.savingcountrymusic.com/destroying-the-dixie-chicks-ten-years-after/ and https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/nov/19/the-dixie-chicks-tour-is-country-music-ready-to-forgive

[16] Quoted in Pratkanis & Aronson (2001) “Age of Propaganda. The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion,” p. 317

[17] Edward Bernays (1928) “Propaganda” available at http://www.historyisaweapon.org/defcon1/bernprop.html